Each move in chess, from the simplest pawn advance to a masterful checkmate, triggers complex neural activity, building resilience against cognitive decline. As we age, our minds, much like a chessboard, face changing challenges. But just as a grandmaster adapts to unexpected tactics, our brains, with the right stimulation, can do the same. This is where chess becomes a weapon—a tool not just for entertainment but for mental longevity. From sharpening memory to enhancing problem-solving, chess can help us win the most important battle of all: keeping our minds active, sharp, and ready to make the next move. Ready to train your brain and outsmart Alzheimer’s? Let’s begin.

The Science of Cognitive Health

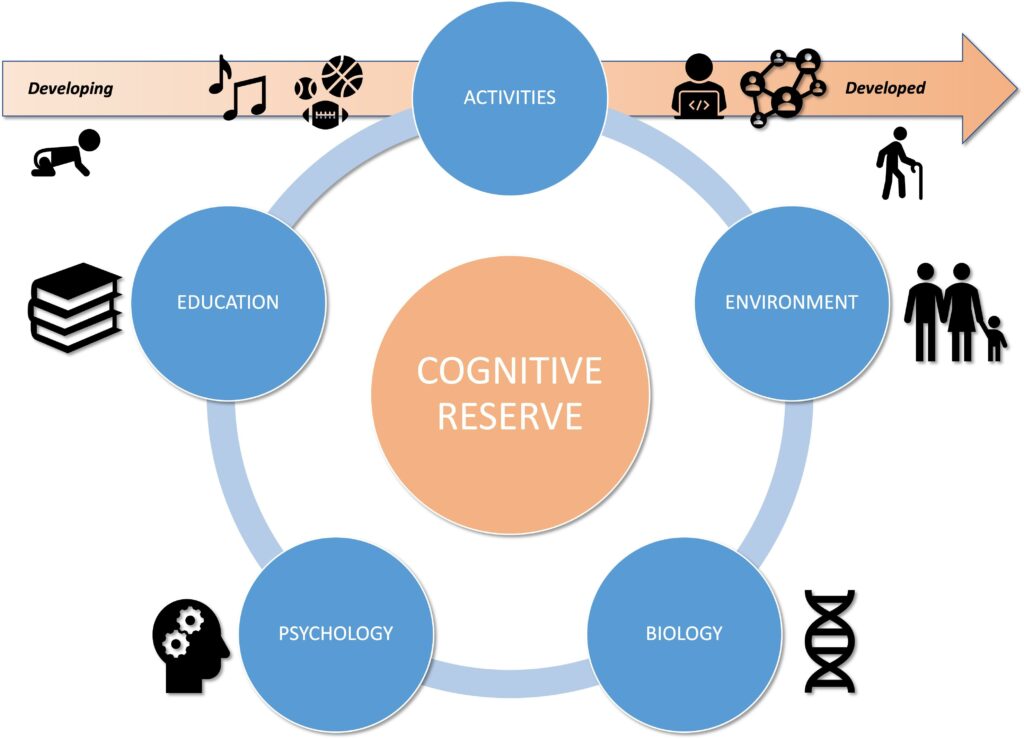

As we age, our brains naturally experience changes, including slower processing, reduced memory retention, and diminished problem-solving abilities. However, scientific studies reveal that the brain is highly adaptable thanks to neuroplasticity, its ability to form new neural connections throughout life. This adaptability means that mental exercises, like playing chess, can stimulate brain regions associated with memory, reasoning, and strategic thinking, potentially delaying cognitive decline. Cognitive reserve—a brain’s resilience against damage—can be built through mentally challenging activities.

Chess, by engaging both hemispheres of the brain, strengthens logical reasoning on the left and creativity on the right. Research has shown that seniors who engage in regular intellectual activities have a lower risk of developing dementia. Moreover, games like chess increase the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein that promotes the growth of new neurons and protects existing ones.

Regular play improves working memory, as players recall past moves and anticipate future strategies, sharpening short-term memory retention. Chess also enhances executive functions—planning, decision-making, and multitasking—critical areas often affected early by Alzheimer’s.

The problem-solving involved in the game mimics real-world scenarios, keeping the brain primed for adaptive thinking. The science is clear: keeping the brain active through complex, rewarding games like chess helps preserve cognitive function well into old age.

How Chess Challenges the Brain

Chess is often referred to as a mental gym because it engages multiple brain regions and cognitive processes, stimulating neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to form and reorganize neural connections. One of the primary cognitive benefits is episodic memory enhancement, as players recall specific board positions, sequences, and game outcomes from past matches. For example, Garry Kasparov famously defeated 32 opponents in a simultaneous exhibition, relying heavily on memory to track multiple boards.

Additionally, pattern recognition activates the brain’s occipital and temporal lobes, allowing players to recognize tactical motifs and common configurations, similar to how grandmasters can visualize a game without seeing the board. Studies show that expert players rely on chunking information, storing patterns as meaningful units rather than individual moves, a cognitive strategy linked to enhanced working memory.

The prefrontal cortex, responsible for executive functions like planning and decision-making, is heavily involved in chess. Players constantly engage in goal-oriented thinking, weighing immediate threats against long-term strategies. For instance, Magnus Carlsen’s ability to outplay opponents in seemingly equal positions demonstrates mastery of strategic foresight, where he envisions multiple future moves, a skill critical in everyday problem-solving. Cognitive flexibility—the ability to adapt to changing conditions—is another key aspect, as players frequently abandon initial plans when their opponent introduces new tactics. This adaptability can help prevent cognitive rigidity, a common symptom of early Alzheimer’s.

The anterior cingulate cortex, associated with error detection and conflict resolution, becomes active when players analyze mistakes or face complex positions requiring trade-offs. Bobby Fischer once described how he would replay losses in his head to identify where his reasoning failed, showcasing the brain’s capacity for post-error adjustments. Abstract reasoning, a function of the parietal lobe, is also central to chess, as players must visualize hypothetical positions without direct sensory input.

Lastly, chess promotes emotional regulation via connections between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, helping players manage stress and decision-making under pressure. This skill was evident when Judit Polgar, one of the greatest female players in history, maintained composure during intense games against top grandmasters. Chess’s ability to train both left-brain analytical functions and right-brain creativity makes it a powerful cognitive exercise, offering protective benefits against neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Chess for Alzheimer’s Prevention: How to Get Started

Chess is a powerful mental exercise, but getting started doesn’t require advanced knowledge or hours of study. With simple, consistent practice, you can reap cognitive benefits while enjoying the game. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

- Learn the Basics: Start Simple

- Familiarize yourself with how each piece moves and basic rules of the game.

- Use online tutorials, beginner apps like Chess.com or Lichess, or books such as Bobby Fischer Teaches Chess.

- Play Regularly for Consistency

- Aim for 20-30 minutes of play daily or 3-4 times per week to keep your brain engaged.

- Use puzzles and tactics trainers available on chess apps to improve problem-solving.

- Join Local or Online Chess Communities

- Social play offers both cognitive stimulation and social interaction, which is important for brain health.

- Look for local chess clubs or join online platforms with live opponents.

- Engage with AI or Play at Your Level

- Start by playing against AI opponents at lower difficulty levels to build confidence.

- Gradually challenge stronger opponents to sharpen your skills.

- Use Chess as a Memory Workout

- Practice recalling previous games, patterns, and tactics.

- Utilize apps with built-in tracking to analyze past games and progress.

- Incorporate Puzzle Solving

- Solve chess puzzles to strengthen working memory and improve pattern recognition.

- Many apps have “daily puzzles” tailored for various skill levels.

- Try Different Variants for Fun

- Variants like blitz (fast chess) or puzzle rush (timed puzzles) offer different types of mental challenges.

- Switching formats keeps the brain flexible and prevents stagnation.

- Set Goals to Stay Motivated

- Whether it’s learning a specific opening or solving a certain number of puzzles, goals help maintain regular practice.

- Track progress using chess apps or journals.

- Join Group Lessons or Take Online Classes

- Learning in groups enhances motivation and understanding through shared knowledge.

- Consider online courses or virtual coaching designed for seniors.

- Combine Chess with a Holistic Brain-Health Routine

- Complement your chess practice with physical exercise, a healthy diet, and good sleep habits.

- Activities like walking or yoga can improve blood flow to the brain, enhancing cognitive performance during chess sessions.